Herping with Gordon Setaro

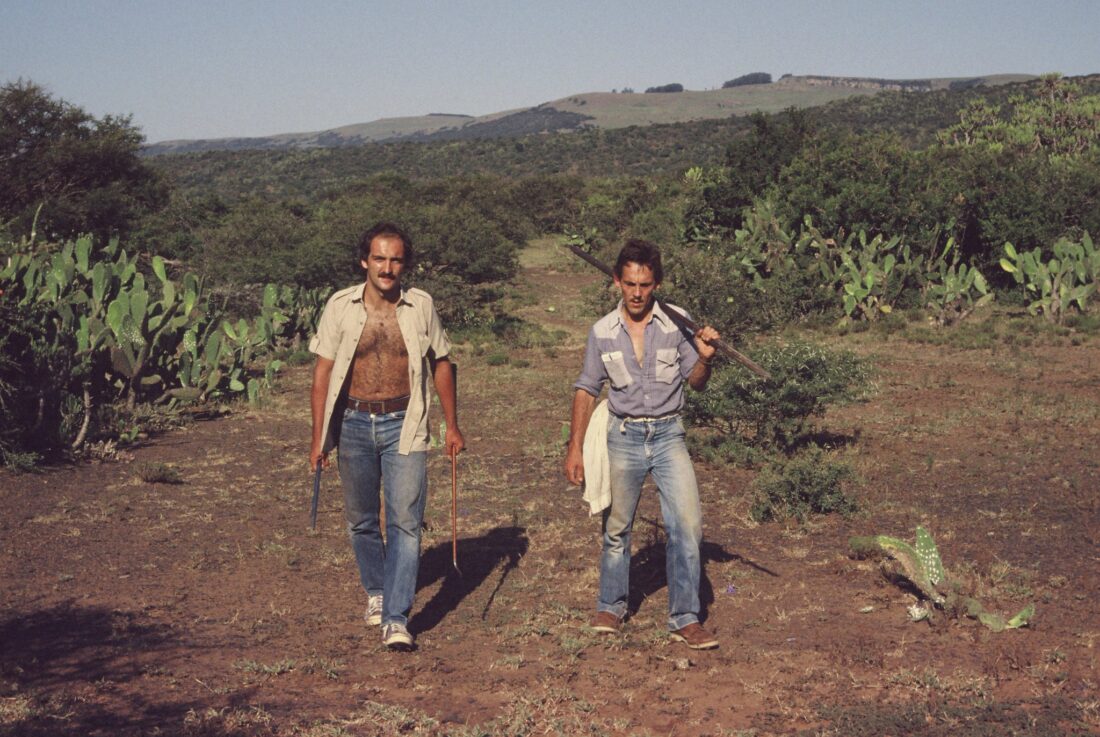

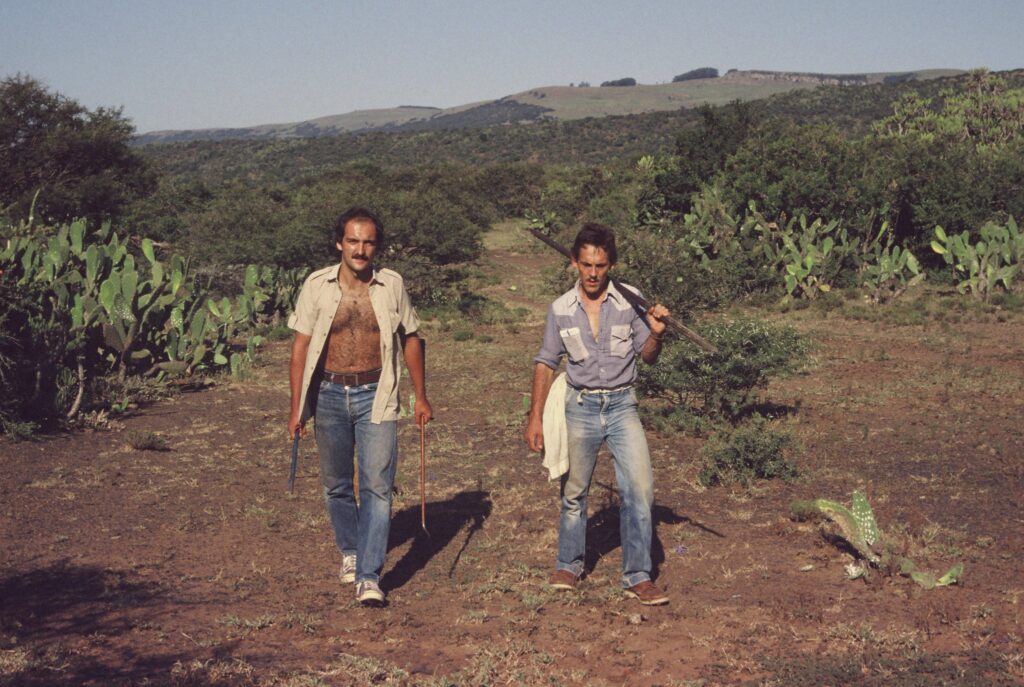

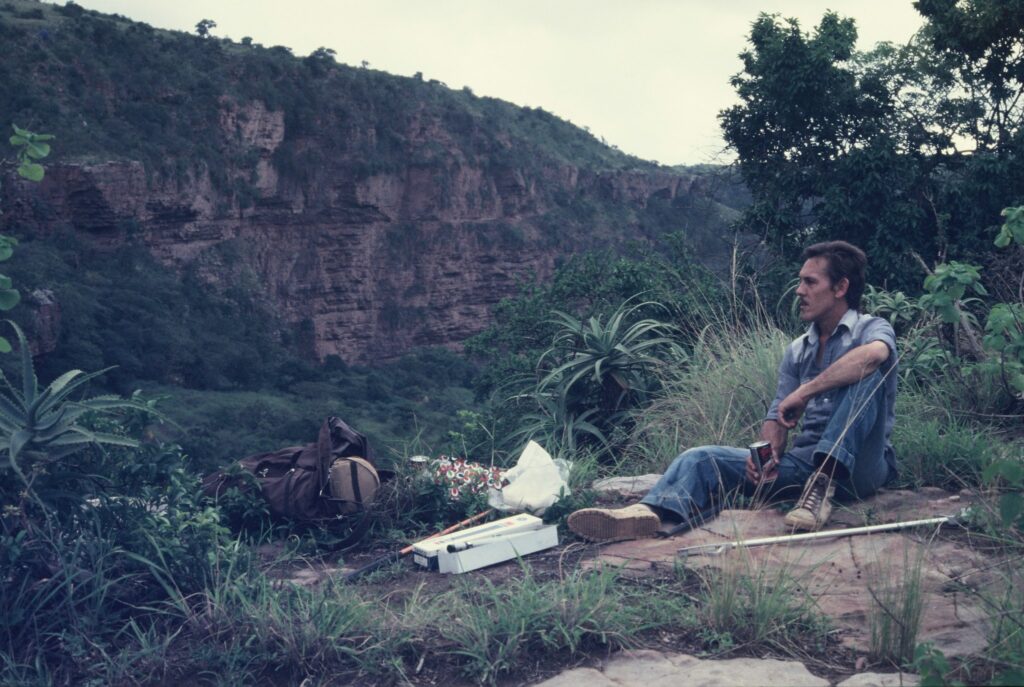

In the Tugela Valley on a stinking hot day back in the 80s.

Back in October 2004 we did a quick trip to the Hoedspruit area with Aaron Bauer. For those of you that do not know Aaron, he is with Villanova University in Pennsylvania and a formidable herpetologist with a special interest in African reptiles, especially geckos.

We collected a number of frogs and reptiles but our mission was to find a flat gecko from Mariepskop and one from the farm Lillie. Aaron was working on a phylogeny of geckos of the genus Afroedura and both of these geckos were mentioned in Niels Jacobsen’s comprehensive study of the reptiles of the Transvaal, done back in the 80s but neither had been described.

Mariepskop was challenging as the rain came poring down and we were freezing. Aaron remained in the vehicle and both Gordon and I went searching, flipping rocks and looking in narrow crevices. We were drenched in no time and lost feeling in our fingers. So we quit and headed back to the vehicle with visibility down to about four meters. As we approached the vehicle we passed a small derelict building with doors and windows removed. I flicked a piece of loose plaster with my stump ripper and a small gecko dropped and was caught in mid air. It was the flat gecko that Aaron needed and is now described as the Mariepskop Flat Gecko (Afroedura maripi).

Our next stop was the farm Lillie which was now fenced in with a game fence and electric fencing. Aaron was very disappointed but as we were about to leave I spotted a game guard and explained that we were looking for a rare gecko that was last seen on the farm back in the 80s. He called the owner and we were given permission to look for the gecko. We caught half a dozen in no time and Aaron had what he needed for DNA. This gecko was subsequently described as the Lillie Flat Gecko (Afroedura granitica). Gordon wandered off, scratching around as he used to do, but returned with a terrifying look on his face. He had stumbled across fresh lion spoor. We were out of there in no time!

The late Gordon Setaro (left) and Aaron Bauer (right) with the suitable habitat for the Lillie Flat Gecko in the background.

About seventeen years ago Jon Warner, one of Graham Alexander’s students, worked on Gaboon Adders in the St Lucia area and a decision was taken to train up a dog to find snakes which would then be fitted with radio transmitters and their movement tracked. An English pointer was acquired and Laser spent several months with the late Dave Fowler, a legendary field dog trainer.

Gordon was given a crash course in dog training and Laser went down to Durban for further training, most of which was done in our property in Umhlanga Rocks where Gordon lived at the time.

Laser was smart. Gordon would hide snakes in the garden in pillow sleeves and upon each find Laser would get a treat. But Gordon soon realised that Laser was a little too smart – smelling pillow sleeves was a lot easier than smelling snakes and he started hiding empty pillow sleeves. A rather disappointed Laser quickly realised that he was not getting treats for finding empty bags and he adapted. But then Gordon realised the next trick – there were only so many hiding places in the garden and Laser would quickly check out all of them without bothering to smell.

Recent research by various contributors from the Alexander Lab at Wits University showed that Puff Adders, while camouflaged, do not emit any smell making it near impossible for predators to smell them out. This may well be the case with Gaboon Adders as well and Laser might not have been that inefficient after all.

Mothers with babies were extremely nervous but Gordon managed to win their trust and could not just touch the babies while the mothers ate the sunflower seeds but he could eventually hold them.

At the same time Gordon started feeding the yellow-billed kites mice and they soon took mice from the palm of his outstretched hand.

And extraordinary man that will be missed by many.

Gordon with Laser in Muldersdrift, training with the late Dave Fowler.

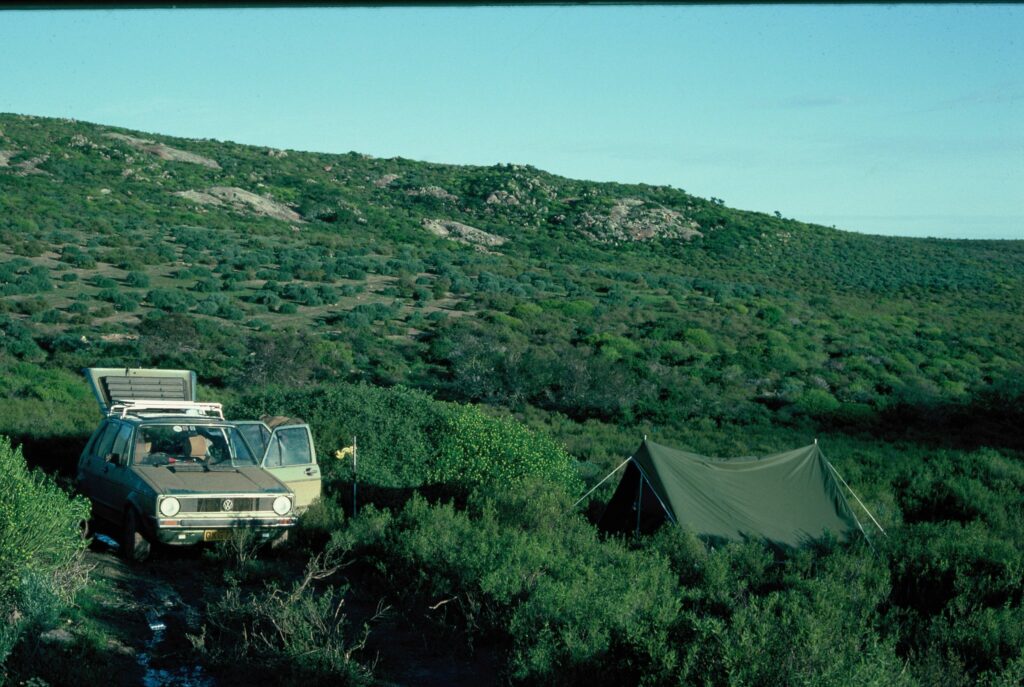

Klaarwater

One of our favourite collecting spots was the cliff face at Klaarwater, Marrianhill, close to where Trappist missionary Father Franz Pfanneur established the Mariannhill Monastery back in 1882. We would drive as far as the Indian trading store and leave our vehicle there, walk down a narrow path that the locals used to get to the bus stop in the mornings, and once we got to the river we went up concrete stairs to reach the pipeline.

Somewhere in the early 1900s (I suspect 1930-1950) a major water pipeline was installed that ran from Shongweni dam down to Durban. At Klaarwater the pipe ran across a west-facing cliff face, and it required quite a bit of construction work. This section of the pipe was laid halfway up the cliff face with four or five meters of cliff face above the pipe and another four or five meters below. The pipe was buried and covered with soil and grass, so we had about half a kilometer of pathway, around two meters wide, to walk along in search of snakes. The cliff face had a good colony of dassies and a very healthy population of Black Mambas.

As the cliff face faced west, the first good bits of sunshine only reached the rocks in mid-morning. Black Mambas would then emerge from the rock crevices and either bask on the pathway or, after a good meal, on low shrubs adjacent to the pathway. We would slowly walk in a northerly direction and look out for mambas. Gordon was of the view that you should never make eye contact with a basking mamba as it would immediately sense danger and slither into the nearest crevice. Our approach was very slow and quiet until the mamba started moving – then you had to be very quick to get a tail tip before the snake was gone.

We lacked snake tongs and hooks in those days and one strategy was to grab the mamba by its tail and when it spun around to bite you would swing it backwards and away from you and then immediately swing the snake again into the opposite direction, keeping the head well away. A few swings and the mamba would soon start tiring out, at which stage you would let it get its head into a shrub. The snake would get its head around a branch, and you then had to apply gentle pressure and get the mamba behind the head and bag it. Crazy times!

We caught many mambas at Klaarwater and the best we managed was six in one morning. While they averaged around 2,2-2,7 m we did manage a few monsters including a 4,2 m mamba that we caught back in 1983, measured and released. We saw the snake more than once, but it took us a while to catch it. A few months before this capture we were there on a hot day with high humidity and the two of us had a rest under a shrub well away from the sun. Gordon dozed off and I was laying on my back when I heard the distress calls of bulbuls and a barbet. I noticed the mamba slowly slithering along the branches of the shrub no more than one meter above us. I alerted Gordon and we could both see the massive belly scales as the snake slowly moved pass us without looking down. We remained frozen until it disappeared.

The longest mamba caught and accurately measured in the past 30-odd years was 3,8 m.

Gordon at Klaarwater

HAA Conference

In October 2004 we headed for Port Elizabeth for a Herpetological Association of Africa conference. The conference was well attended, and the big names were there – Aaron Bauer, the late Bill Branch, the late Wulf Haacke and the late Don Broadley.

Gordon joined me on this trip, probably one of the first such conferences that he attended. We met with Graham Alexander and his crew from Wits University somewhere in the Eastern Cape and scratched around. There were several interesting reptile encounters including a Sundevall’s Shovel-snout, a Yellow-bellied House snake and this stunning Rock Monitor photographed with Gordon and a youthful Bryan Maritz.

Gordon and Bryan Maritz

Namaqualand

Gordon loved Namaqualand but seldom spent time on the coast. On a trip with Paul Moler and Rob Deans we got Gordon down to McDougalls Bay and he loved it. Digging out fossorial skinks and tracking Namaqua Dwarf Adders had him going for hours. On this trip we stayed at Ratelkraal, a farm owned by Kallie and Loenkie Kennedy but now part of Goegap Reserve.

This was in November of 2005 and I cannot recall what snakes we encountered and had to ask Rob who clearly remembers more than I do. I am sure Paul will have more to add.

We found three Many-horned Adders (Bitis cornuta), six Horned Adders (Bitis caudalis), one Spotted Rock Snake (Lamprophis guttatus), one Common Egg-eater (Dasypletis scabra), one Dwarf Beaked Snake (Dispina multimaculata), a Beetz’s Tiger Snake (Telescopus beetzii) and a few Cape Coral Snakes (Aspidelaps lubricus lubricus).

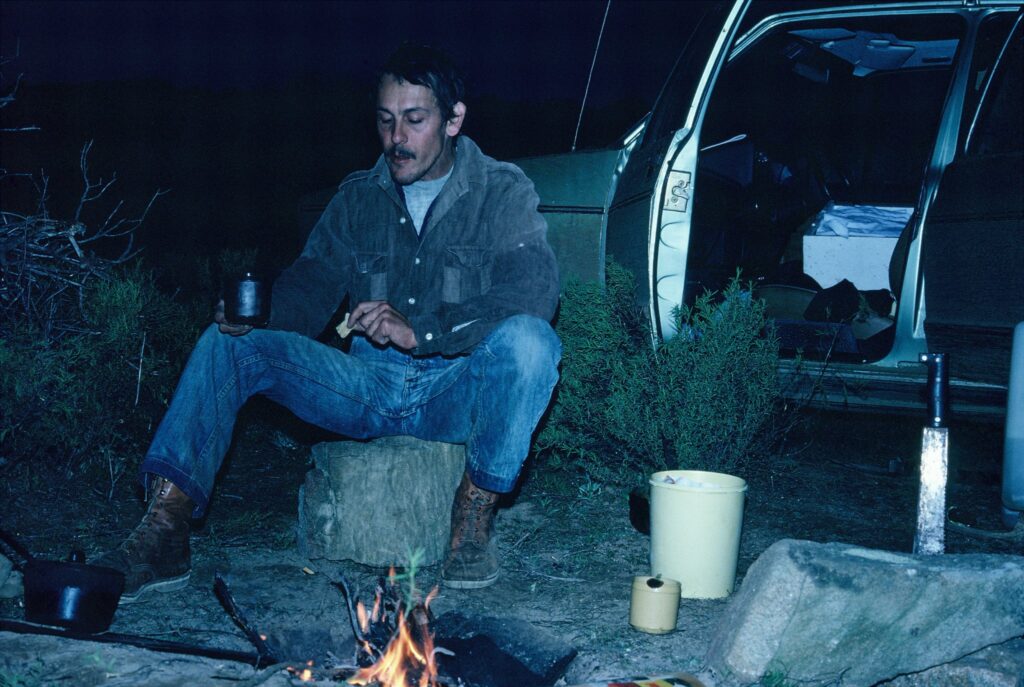

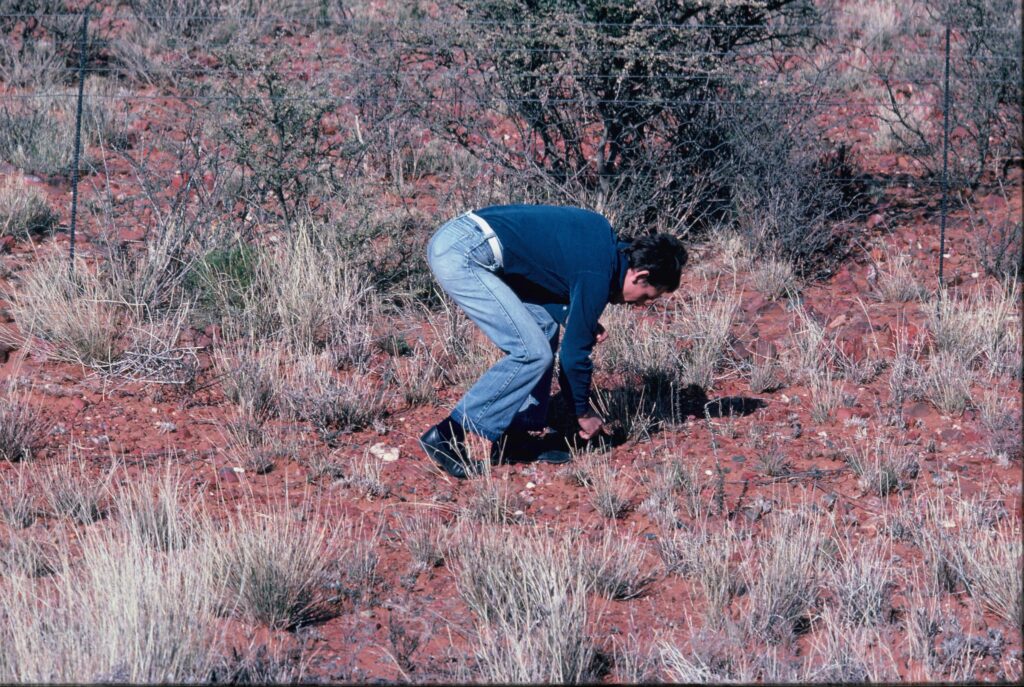

Gordon Setaro somewhere in the Northern Cape on one of many trips to Namaqualand.

Gordon and my good friend Graham Alexander

Gordon in the snow

Back in the 80s we did quite a bit of scratching around in Lesotho and I times Gordon would stay high up in the mountains in eastern Lesotho for two or three months, sleeping in a primitive shepherd’s hut as the shepherds moved west to lower elevations in winter. It was freezing cold, and waterfalls would ice up.

In this photograph we had a day or two and had to make the best of our time. Conditions were not ideal, and we found very few reptiles. An essential piece of equipment in those days was a crowbar but the long crowbars were very heavy and, having six sides, left you with blisters. It was particularly problematic when you tried to lift very large rocks and the rocks slipped. But Gordon had an answer. He took two motorcycle shocks, machined them so that they screwed together and locked with an allen key. For the tip he took a concrete chisel which he machined and mounted on a bearing. Slipping rocks no longer posed a problem as only the front tip would swivel when large rocks slipped and not the entire crowbar.

Catching reptiles

When it comes to the actual catching of reptiles, Gordon had many tricks. Water monitors were grabbed by the tail and quickly spun around to keep the biting bit well away from his body. He would then stand on the neck and quickly grab the lizard behind he neck in a manner that it couldn’t bite or scratch. Tree agamas were another story. Once we spotted a large male about a meter or so off the ground on a tree trunk, Gordon would circle the tree and approach it from the opposite side. Then one of two strategies – he would ask me to show him how high the agama was and would then quickly grab around the tree trunk with both hands. Otherwise he would stand against the tree and I had to run towards the agama. It would run around the other side of the tree, onto Gordon’s back and he would step away from the tree and grab as the lizard jumped off his head towards the tree.

In the Drakensberg he would catch a large crag lizard and tie a piece of sting around it. He would then let it run into any rock crevice and females would come running out, terrified by the presence of a strange male while males would come rolling out fighting the new male.

He once grabbed a large Black Mamba by the tail and as it spun around to bite he threw it my way shouting mamba and I had a 2,5 m mamba flying my way like a boomerang!

Underberg

Gordon loved collecting in the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands, and he had a few favourite spots. This farm near Underberg has the perfect habitat for a variety of snakes – largely Spotted Skaapstekers, Brown Water Snakes, Olive Snakes, Brown House Snakes, and Rinkhals. A stream passed through the farm and at one section slates of rocks were exposed on the banks and slid down during heavy rains. These flat rocks provided good shelter for a variety of snakes.

We did well on this trip and found several Brown Water Snakes, Olive Snakes and Spotted Skaapstekers coiled around their eggs. On a previous trip in September Gordon broke all records, finding just over 160 snakes on a weekend. The snakes were active but surprised with a late bout of snow and they scattered for shelter. Each rock that Gordon flipped had a several lethargic snakes and he literally grabbed bunches of snakes and quickly took them away from the river.